Ophthalmologic complications are common in critically ill patients requiring prolonged ventilation. These complications are caused by improper eye care and impaired functioning of normal mechanisms that protect the eye from dehydration and abrasion. In the era of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19), where approximately 30% of hospitalized patients and 5% of overall cases require ventilation for acute respiratory failure [2], important measures should be taken to identify, address, and minimize ocular complications.

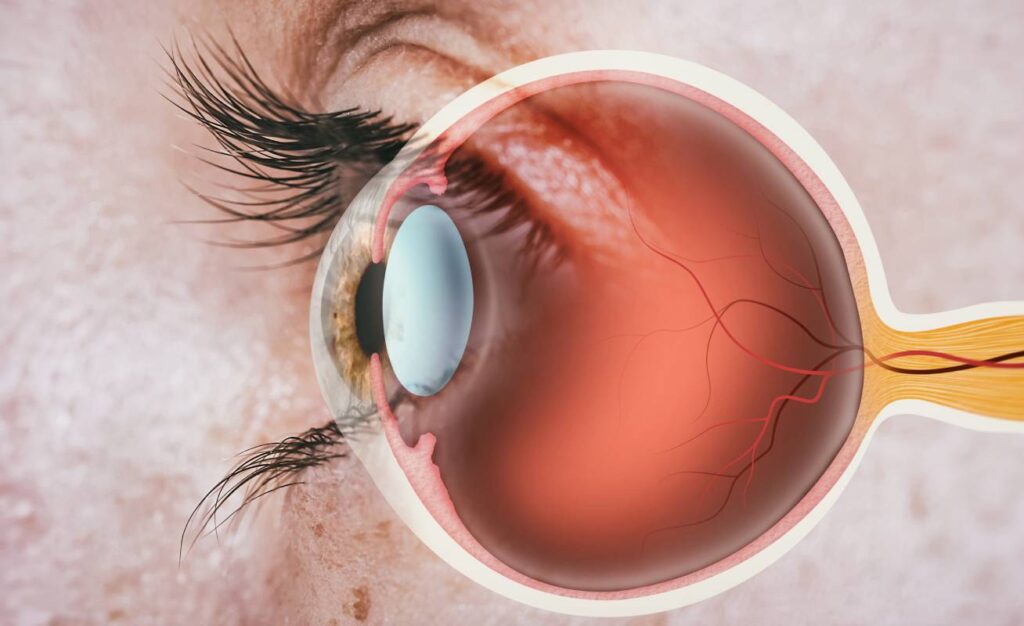

Under normal circumstances, eyelid closure and blinking prevent dehydration and dryness of the outer surface of cornea. However, in critically ill patients, these protective mechanisms may be altered because of the use of sedation and muscle relaxants to facilitate ventilation, impairing eyelid muscles and leading to incomplete closure of the eyelids, which can result in ocular surface complications [1,2]. In addition to muscle relaxants, patients with fluid imbalances in the ICU can have conjunctival and lid swelling, known as chemosis, which also prevents complete closure of the eye [2]. Lastly, critically ill patients may experience impaired tear formation. Tears are important for lubricating eyelids, washing away foreign material and debris, and preventing organisms from adhering to the eye’s surface; tears also deliver oxygen to the outer surface of the eye and deliver white blood cells to injured areas [1].

Inadequate lid closure, or lagophthalmos, is a frequent complication of sedated patients, especially those needing prolonged ventilation, and can lead to many surface ocular complications including exposure keratopathy and microbial keratitis. Exposure keratopathy, a problem reported in 20 to 60% of ventilated patients, refers to damage to the corneal epithelium caused by incomplete lid closure. Exposure keratopathy can lead to corneal scarring and perforation. Microbial infection of the cornea, referred to as microbial keratitis, may occur secondary to exposure keratopathy. Microbial colonization of the cornea is associated with prolonged stays in critical care units and high-dose steroids or immunosuppression in general [2]. The ICU is also an environment rich in pathogens that can colonize exposed surfaces of the eye and lead to infection [1].

Lagophthalmos, exposure keratopathy and microbial keratitis are highly preventable eye-surface complications associated with prolonged ventilation. One study found that conducting eye exams in ICU patients twice per week could lead to identification and prevention of exposure keratopathy. This study by McHugh et al., demonstrated that ICU physicians, with no prior experience in ophthalmology, could screen for exposure keratopathy with reasonable sensitivity (77.8%) and specificity (96.7%) using a simple pen torch with a blue filter and fluorescein dye. Other methods of eye protection include using preservative-free ocular lubricants or drops and proper lid taping. Studies have shown that using moisture chambers and polyethylene films can confer greater protection than using lubricant drops [2]. Finally, one study found that Kerrapro, a silicone-based material used commonly in critical care settings to prevent pressure ulcers, can also aid with mechanical eyelid closure and prevent direct globe compression in patients mechanically ventilated in the prone position [2]. In summary, though ocular surface complications are common in ICU settings, they are highly preventable when regularly screened for and managed prophylactically with lubricants, gels, and proper lid-taping.

References

- Marshall, A. P., Elliott, R., Rolls, K., Schacht, S., & Boyle, M. (2008). Eyecare in the critically ill: clinical practice guideline. Australian Critical Care, 21[2], 97-109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2007.10.002

- Sanghi, P., Malik, M., Hossain, I. T., & Manzouri, B. (2021). Ocular complications in the prone position in the critical care setting: the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of intensive care medicine, 36(3), 361-372. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885066620959031

- McHugh J, Alexander P, Kalhoro A, Ionides A. Screening for ocular surface disease in the intensive care unit. Eye (Lond). 2008 Dec;22(12):1465-8. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702930. Epub 2007 Aug 24. PMID: 17721505.